IDP News Issue No. 20

Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries

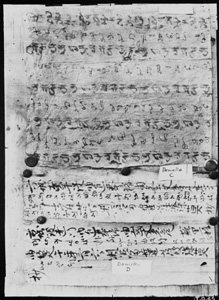

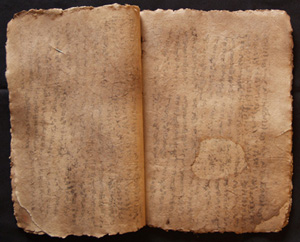

Left:Photograph taken of one of the forged manuscripts which Stein acquired on his 4th Central Asian expedition. The top manuscript, Domoko B4, contains text in two scripts, one thick and one thin, both resembling Brahmi but without any meaning (see p. 8). The bottom two manuscripts, Domoko C and D are Chinese/Khotanese bilingual. The British Library, T.O.45 (Photo. 392/52(39).

Forgery is a story with all the elements to grip the popular imagination: greed, large sums of money, deceit, sometime violence and, not least, the ability of the ordinary man to bamboozle the greatest expert or most lofty institution. The story of Central Asian Dunhuang manuscript forgeries contains all these elements and, despite almost nine decades having passed since the forgeries started to be produced, the story is yet to be concluded. Whether this is due more to curators' complacency or the forgers' skill is a matter of debate, but the fact remains that we still cannot say with any certainty whether there are large number of forgeries among the Dunhuang manuscripts now in collections world-wide, let alone give a foolproof method of detecting them or explain fully how and by whom they were made.

ome contributors to this collection1 argue that this is overly cautious, that they can distinguish forgery without any doubt, and that it is certain that most of the manuscripts collected after the early expeditions, namely those in St. Petersburg, Japan and a portion of the London collection, are forged. Other contributors argue, just as vociferously, that most of these manuscripts are genuine. The scientists would dismiss both claims as subjective and therefore unverifiable and turn to the need for 'objective' testing before proof can be claimed either way. These differences reveal just how little of the story has yet been told and how far there is to go. The purpose of the conference held in June 1997 and these resulting papers, therefore, is not to make decisions but simply to open the debate. For the conference was the first public discussion of this issue.

The Dispersal of the Dunhuang Manuscripts

Cave 17 at Dunhuang was probably discovered in June 1900, The self-appointed guardian of the caves, Wang Yuanlu, presented a few manuscripts and paintings to local officials. Stein and Pelliot acquired many more and, in 1909, Fu Baoshu, an official in the Ministry of Education, was dispatched to Dunhuang with the order to transport all the manuscripts left in cave 17 to the Ministry for safekeeping. They arrived in 1910. In the same year Fu Baoshu was arrested. Most scholars have accepted the version of these events given by Luo Zhenyu in 1927, in which he claimed that a famous bibliophile, Li Shengduo, and several others arranged to steal manuscripts while they were in transit. However, Rong Xinjiang challenges this and makes excellent use of contemporary historical sources in Peking University library to argue that the manuscripts reached Beijing intact. However, he continues, there is evidence to suggest that Li Shengduo arranged the theft later, when the manuscripts were already in the Ministry (Li Shengduo was a high official there) and after they had been seen by visiting Japanese scholars. The son of a friend of Li's later wrote that Chen Yi'an, Li's nephew, made copies of the manuscripts in his uncle's collection to earn money.

Copying manuscripts and works of art has a long tradition in China. Monique Cohen enumerates the various methods in use, including copying from sight, tracing, tracing the outline and imitation. The aim was not to deceive - this was not a process of forgery - but to learn. The same method was also used in the western artistic tradition. But some artists, both eastern and western, seem to take special pleasure in fooling experts and others. A paradigm is the case of Zhang Daqian, a Chinese artist discussed in Roderick Whitfield's paper. He spent time at Dunhuang with his students making copies of the wall paintings, but also, according to Whitfield, seems to have taken delight in making Dunhuang forgeries of silk paintings.

Cohen also enumerates Zhang Daqian's talents as a forger, and places him in a long tradition of forgery masters in China. Copies were made from the fourth to fifth centuries but, as a number of other authors have pointed out, it is the development of an art market which acts as a catalyst for forging rather than copying. In China there was a market for calligraphy from the fifth century, for painting by the eighth, and for artefacts by the eleventh, but the Chinese collector came into his own in the sixteenth century. This was when connoisseurship became a high calling for the Confucian gentlemen. The Chinese word for connoisseurship is composed of two elements which mean, respectively, 'to discriminate on the grounds of quality' and ' to distinguish true from false'. Chinese connoisseurs were therefore alert to the possibility of artistic forgeries: indeed, they were often the perpetrators.

Forging of texts is a more complex matter. There may be no monetary benefit for the forger of an historical text who wishes, for whatever reason, to create history, nor may there be any personal credit. Examples of this type of forgery abound in Chinese tradition, from the forging of ancient literary and philosophical texts probably as early as the latter part of the first millennium BC, to the creation of apocryphal sutra throughout the first millennium AD. The Dunhuang manuscripts, however, occupy an interesting position which is neither wholly akin to works of art nor to texts, but something of each. This ambivalence is apparent in their study. As Lancaster notes, early scholarship was interested only in the text so that microfilms were deemed sufficient. This is still the case for many scholars.

The attitude of textual scholars contrasts with paper historians and others who are only interested in the manuscript as an object and may not even be able to read the text. When it comes to looking at the manuscripts from the point of view of forgeries, however, it is apparent that they are treated very much as objects — as works of art (a situation very different from Indian manuscripts, as Lancaster points out). As far as we know, the texts of forged manuscripts are not unique or variant: they are simply reproductions of existing texts. The forgers were not concerned to create history — at least, not by producing variant textual sources — nor, it would appear, were they interested in displaying their personal skills. The majority of Dunhuang forgeries were probably made for one reason: money.

Lancaster discusses this and makes the salient point that, despite China becoming a print culture at a very early stage, the skills for creating manuscripts did not die out. Calligraphy remained a high art and manuscript copies of texts were needed for production of the woodblock for carving. Nevertheless, as a number of authors stress, the skills necessary for producing a good copy of a Dunhuang manuscript were in fairly limited supply. Fang Guangchang, in his paper, suggests that the forger required 'considerable experience in handling genuine Dunhuang manuscripts and to have researched their form and content; ... a detailed knowledge of classical Chinese history; ...well-grounded brushwork skills; ... a solid understanding of mounting techniques; and, finally, a good knowledge of Buddhism.'

In the case of Dunhuang manuscripts, the text is not a major issue since most of the forgeries appear to be of canonical Buddhist works. Even if the forgers did not have genuine manuscripts to copy from, they had copies of the Buddhist canon dating almost as far back as the manuscripts, and whether, therefore, a good knowledge of Buddhism was strictly necessary is a moot point: a scribe should be able to copy anything, whether or not he understands it. However, the importance of the text should not be entirely disregarded. Vetch's paper is a model of historical research based on a forensic examination of the text, and shows us how far a well-trained scholar can proceed using these traditional research methods. In her paper, Scherrer-Schaub also uses historical analysis of Tibetan Buddhist texts for dating, but reinforces it with philological, palaeographical, and codicological investigation. Systematic philological analysis of Chinese Buddhist texts is still to be done and, as Lancaster says, 'Buddhist scholars have given almost all their attention to the printed versions and the lack of comparable attempts to study the stemma of readings from Buddhist Chinese manuscripts means it will take many years to establish this.'

Unfortunately, the early development of printing has resulted in a comparative lack of development in another discipline concerning both Chinese and Tibetan manuscripts which, in the west, is an important tool in the discovery of forgeries: palaeography. Another factor in this, as both Drege and Lancaster note, is that the study of handwriting was approached through calligraphy, that is, as an artistic rather than a scribal tradition.

When Were Forgeries Made?

To return to the matter of if, when, and how Dunhuang forgeries were made, few would dispute that some were produced between 1920 and 1949 when the value of the manuscripts was realized by a new class of collectors and there were still few enough manuscripts in circulation for the forgers' work to escape detection. Fang Guangchang argues that the market ended after 1949 because the price of manuscripts was state controlled and, consequently, low. However, this is to underestimate the ingenuity of man. Although required to sell important historical artefacts, such as Dunhuang manuscripts, to the state, this does not mean that everyone did so. There was a ready market among Japanese and US collectors. There is also the possibility that forgeries continued to be made outside China. But the main issue here concerns earlier forgeries and there are several questions remaining unanswered: whether forgeries were made locally to Dunhuang and, if so, when, in what numbers and by whom?

Cohen argues that it is difficult to imagine forgeries being produced before 1909 because, up to then the manuscripts were not worth a great deal and, in any case, there was a ready supply. However, some Japanese scholars, led by the doubts of Fujieda, have challenged the authenticity of all manuscripts acquired local to Dunhuang after the cave was cleared in 1910. This would include all the Russian collection, all the Japanese Otani manuscripts, and those 600-odd scrolls acquired by Stein on his third expedition and his second visit to Dunhuang in 1913. Ishizuka uses an afterword in his conference paper to deny the suggestion that any manuscripts acquired before then are forged, and overwhelmingly scholars have accepted that the bulk of the Stein collection and the entire Pelliot collection, along with the original Beijing collection (not including manuscripts acquired after 1910), are indubitably genuine and can be used as a baseline. But to be consistently rigorous, even this assumption needs to be re-examined, especially as it is the foundation on which all knowledge of the genuine manuscripts is built.

The question after this is whether some forgeries started to be made before 1909. Cohen's arguments - lack of a market and lack of skills - are persuasive but not final. The finds were known about by local officials and scholars: the presentation of paintings from the cave to local officials shows that they were considered to have value. Moreover, locals were well aware of the interest of foreign archaeologists in manuscripts. And the ready supply was only 'ready' to Wang Yuanlu, so that anyone else wishing to trade in these manuscripts would have to produce their own. Although the probabilities are against forgeries being made at this time, it cannot, I would argue, be entirely dismissed.

The Expert's Eye versus Science

In their paper Fields and Seddon accept the importance of the expert's 'eye' and other subjective evidence, but point out that such evidence 'is never without distortion by personal feeling and prejudices' and that 'for a true scientific analysis ... we must rely most heavily on objective evidence.' Outnumbered in the conference, their passionate justification of the primacy of science is perhaps understandable, but it must be remembered that science can be a false friend. Firstly, of course, there is the fact that there is good and bad science, and the difference between them depends on the scientists.

Second, science can be used to deceive as well as elucidate and we must never be blind to its limitations. In the nineteenth century when photography was developed it was really believed that it could not lie: it was a scientific procedure producing objective results. The photographs of fairies at the bottom of the garden soon showed the paucity of this argument. Objective tests in common use today, such as thermoluminensce, are also open to the forger's ingenuity. In the case of the manuscripts, given that monasteries and other institutions in China often kept supplies of old paper, it is possible (although unlikely given the age and therefore the value of such paper) that some of the forged manuscripts were written on original paper and that radiocarbon testing would give a plausible date for the manuscript being original. A negative test, of course, would prove it to be a fake.

Whereas science is concerned, many of the methods being developed will be of great use in helping us understand better genuine manuscripts. Some tests, however, will always be more focused on authentication, such as radiocarbon dating. This is both destructive and comparatively expensive - at least for public institutions where most manuscripts are held. Like thermoluminesense, it is easy to see it becoming a test used by collectors in the marketplace to verify their products once the forgery issue becomes common currency and the conspiracy of silence, so long dominant in this field, is broken, but it is another matter whether public institutions will ever be able to justify widespread radiocarbon dating. It is more probable that it will be used for random testing to corroborate other evidence.

But this is still a long way off. The papers in this collection, as mentioned previously, open the debate and pose questions. Now that this issue is in the public sphere and all those involved — the curators, conservators, scholars and scientists — have recognized the need to corroborate on further research, it is to be hoped that the advance in scholarship will be rapid. A full understanding of the historical circumstances of the discovery and dispersal of the manuscripts and a clarification of the provenance of all those manuscripts previously labelled as from Dunhuang is long overdue, and this should be the first aim of future research.

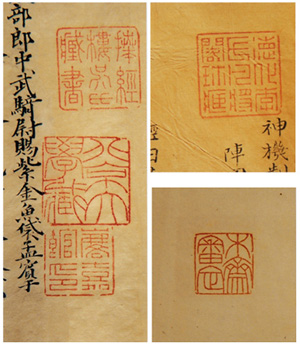

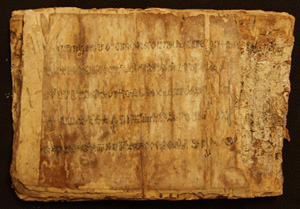

Right:New panel of paper added in middle of original manuscript, The National Library of China, gang 74.

Notes

1. This is a condensation of Dr Susan Whitfield's introduction to Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries (The British Library, 2002: (see Publications page).

Islam Akhun's Forgeries 1895-7

Hoernle's first major publication of the manuscripts in what he called the British Collection of Antiquities from Central Asia was in 1897.1 This was a description of three collections acquired in 1895 and 1896. Besides giving detailed descriptions of the manuscripts themselves, Hoernle identified them mostly as being in Sanskrit and a 'non-Sanskritic' (i.e. Khotanese) language in Brahmi script, and gave transcriptions of them. However sets 2-6 of the last collection (Macartney1) were:

written in characters which are either quite unknown to me, or with which I am too imperfectly acquainted to attempt a ready reading in the scanty leisure that my regular official duties allow me ... My hope is that among those of my fellow-labourers who have made the languages of Central Asia their speciality, there maybe some who may be able to recognize and identify the characters and language of these curious documents.2

By 1899, the British Collection possessed in addition 45 block-prints which had been purchased on behalf of the Govt. of India by George Macartney, at the time Special Assistant for Chinese affairs at Kashgar, and Capt. Godfrey, Assistant to the Resident at Kashmir, and Joint-Commissioner at Ladak.3

Left:Typical Islam Akhun block-printed forgery. The British Library, Or.13873/21

The manuscripts included examples of texts in white ink which resembled Uighur script, some in Chinese style characters, and others in what Hoernle euphemistically described as a very cursive form of Brahmi. Some were single sheets, but others had been bound in a primitive codex type style. Samples of the best preserved were printed.4 In his 1899 article, Hoernle gave an extensive account of the blockprints.5 They all, except for one, had bindings similar to European books. They were fastened with copper pegs (30), twists of paper (12), and with thread (2). Hoernle divided them into 9 different groups based on the kind of scripts in which they were written, which resembled Kharosthi, Indian and Central Asian Brahmi, Tibetan, Uighur, Persian and Chinese. But despite his detailed analysis, Hoernle was still unable to interpret them.

Because of their resemblance to known scripts, Hoernle sent samples of the blockprints to other scholars. On 21 July 1899, for example, he sent Dr. E. West six which seemed to imitate Pahlavi writing.6 West wrote, in July 1901:

I find that the Pahlavi words I have collected form one-twelfth of your large MS., contain 13, out of 15, Pahlavi characters, and represent 27 out of the 33 known Pahlavi sounds. So that a twelfth part of the MS. has supplied five-sixths of the Pahlavi alphabet and sounds. But it has not supplied a single intelligible clause of a sentence.7

At various times Hoernle questioned the authenticity of the blockprints, quoting a lengthy correspondence with Rev. Magnus Bäcklund, the Swedish Missionary in Kashgar, who had written to him on 29 June 1898, describing an incident earlier in the year when Islam Akhun had offered him three books. Islam Akhun had appeared uneasy while the books were being examined, and accepted half of his original price without haggling. After he had left, one of the servants said, as reported by Bäcklund:

Sahib, I want to tell you that these books are not so old as they are pretended to be. As I know how they are prepared, I wish to inform you of it. When I lived in Khotan, I wished very much to enter the business, but was always shut out and could even get no information about the books. At last I consulted my mother about it; and she advised me to try and find it out of a boy with whom I was on very intimate terms, and who was the son of the headman of this business. So, one day I asked him, how they got these books, and he plainly told me that his father had the blocks prepared by a cotton-printer.8

However, taking other considerations into account, in 1899 Hoernle believed that the manuscripts were genuine, as were most, if not all, of the block-prints. If any were forgeries, he argued, they could only be duplicates of genuine ones.

By 1901, when he wrote part II of his report, Hoernle had changed his mind. During his first Central Asian expedition (1900-01), Stein had tried unsuccessfully to locate all the sites described in detail as find-places by Islam Akhun. At the end of his visit, he confronted him in Khotan and obtained a full confession and account of how the forgeries were made.9 All the manuscripts in 'unknown characters' and all the blockprints were modern fabrications of Islam Akhun and his colleagues. Some attempts had also been made at forging pottery and other antiquities.10

The manuscript production had begun early in 1895 but was abandoned in favour of blockprints about two years later. Sheets of modern paper had been dyed yellow or light brown, and when dry were written or printed on. They were then aged by being smoked and were bound. The finished volumes were sprinkled with sand to make them look as if they had been dug up from the desert.

The early manuscripts had been written carefully, but the blockprints were done comparatively carelessly. Hoernle himself, comparing a word from a blockprint with a one in a genuine Brahmi manuscript, re-examined it in a mirror and recognised it immediately as the reverse image. The whole document had evidently been cut on wood copying some genuine and some false letters, without the realisation that when printed it would appear in reverse!

Brahmi forgeries from Stein's 4th Expedition 1930-31

Considering that Stein was one of those most suspicious of the manuscripts and books in 'unknown characters' in the British Collection, it is surprising that several of the documents he acquired on his fourth expedition to Central Asia were themselves forgeries.

Stein's fourth expedition was beset with difficulties from start to finish,11 but he eventually reached Kashgar early in October 1930.12 Between mid-November and February 1931 he visited Khotan, Domoko and Niya where he was able to carry out some archaeological work. On reaching Charchan in February 1931, he was ordered to return to India immediately, and went back to Kashgar along the northern side of the Taklamakan Desert, collecting data on hydrographical changes in the area and establishing exact longitudes round the Tarim Basin.

During the Southern part of his journey Stein purchased 2 Kharosthi woodslips, 3 packets of paper manuscript fragments in Indian script, 1 packet of paper manuscript fragments in Indian and Tibetan scripts, and a packet of small manuscript fragments (Indian) with beads and wood carving. At Niya he found 46 Kharosthi and 27 Chinese woodslips on or near the surface.13

On his return to Kashgar in April Stein arranged with Capt. George Sherriff14 to take photographs of the manuscripts, in case he was prevented from taking the finds themselves to London for further examination. In the event, the antiquities were handed over to the Kashgar Taoyin, on 21 Nov. 1931 by Sherriff's successor, N Fitzmaurice.15

Stein had several sets made of the photographs. One set of prints and negatives are preserved in the British Library.16 Another set of the Brahmi prints is preserved in the late Professor Sir Harold Bailey's papers preserved at the Ancient India and Iran Trust, Cambridge.

Professor Bailey's Work on the Brahmi Photographs

The history of the decipherment and publication of the Khotanese documents among the Stein photographs is described in Wang Jiqing's article, but some additional material has come to light in Sir Harold Bailey's papers. When he returned to England, Stein wrote from Oxford on 27 April 1931 to Dr. L. D. Barnett, at the British Museum enclosing prints from photographs taken at Kashgar in May 1931:

of Brahmi MS. Fragments I had been able to acquire in the preceding autumn on my passage through Domoko, Achma and Keriya in the Khotan region. The originals which in all probability had been dug up at late Buddhist period ruins of those tracts had to be left at the Consulate General Kashgar. They are likely to have since been sold ... or destroyed during the Muhammadan rising in Chinese Turkestan.

He adds that the negatives of all the photographs were available 'at the collection of my finds, 1932-4, now in the Ceramic Basement under Andrews' care.' He asked Barnett to submit the material to Mr. Bailey or any other interested scholars, mentioning that duplicate prints '7 from MS. remains obtained at Achma; 9 from Domoko; I from Keriya ... are available at Mrs. Allen's house where I write this.'

Stein himself sent samples of the prints to Prof. Sten Konow in Oslo in 1931 inviting him to work on them. In a letter discovered by Prof. P.O. Skjærvø17 at the Institute for Indian and Iranian Studies (Indoiransk Institutt), University in Oslo, dated 4 November 4 1931 (c/o Messrs Thomas Cook & Sons, Bombay) written on his way to Lahore Stein wrote:

I am very grateful for your willingness to take up the study of those manuscript remains I collected but had to leave behind at Kashgar. I hope to secure improved imprints from the Photographic Department of the Thomason Civil Engineering College, Roorkee,18 They have been rather successful with negatives of Chinese documents, I fully appreciate the difficulties besetting interpretation of such documents. But some pieces seem to contain Buddhist text fragments.

Konow apparently never produced any results, so on 29 April 1935 Barnett wrote, enclosing prints, asking Bailey to describe their contents. Stein independently wrote to Bailey with the same request on 6 Dec. 1937.19 Bailey replied the next day explaining that Dr. Barnett had already sent him prints over a year ago. 'Three or four are official documents but several are in a variety of brahmi script not yet read with certainty.'20

Bailey worked on the photographs between 1945-49 when he was preparing volume II of Khotanese Texts, (Cambridge, 1954). There, on pp. 62-3, he published the Khotanese text of five of the documents, and photographs of them, plates XCV and XCVI, in vol IV of Saka Documents (London, 1967). They were:

Achma (Photo 392/57 T.O. 20)

Domoko (Dumaqu) A4 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 34)

Domoko (Dumaqu) C (Photo 392/57 T.O. 45 (see p. 1)

Domoko (Dumaqu) D. (Photo 392/57 T.O. 45 (see p. 1)

Domoko (Dumaqu) F (Photo 392/57 T.O. 46)

However, his dated notes on the other texts show that he was only able to read occasional letters.

The Forgeries

The other Brahmi documents are:

Achma 1, 3 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 35-36)

Achma 4 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 32-33)

Achma 5 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 44)

Achma 6 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 40)

Domoko A.1-3 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 29-31)

Domoko B1-4 (Photo 392/57 T.O. 41-43, 45 (see p.1)

(no site no.) (Photo 392/57 T.O. 39)

The Achma documents are written in a very thin spidery script, and the Domoko ones are 'bilingual' with lines in the same script alternating with a second thicker 'formal' type script. The unnumbered one, perhaps from Keriya,21 is of the formal type. According to Professor Skjærvø, who recently re-examined the prints during his work on the Khotanese catalogue (see above), the thicker script may have been intended to imitate the 'literary' Brahmi script of the sutra fragments. The thinner one copies that of the documents. The mixed texts do not really have any models, unless it is the Chinese-Khotanese bilinguals (Dom C).

The thicker script contains signs that recall genuine Brahmi, but any attempt at reading them fails at once. The thinner script contains letters that are very similar to genuine ones, but the scribe did not recognise the characteristic features of each akshara. For instance, he did not realize that they are all aligned according to a base/top line, with some parts above it and some below, with the result that the tops of the vowel signs are aligned in a nonsensical way with the tops of letters without any vowel signs.

Ursula Sims-Williams is curator of the India Office Persian material at the British Library.

Notes

1. A.F.R. Hoernle, 'Three further collections of ancient manuscripts from Central Asia', JASB 66 (1897), pp. 213-60 (Hoernle, 1897).

2. Hoernle, 1897, p. 250.

3. A.F.R. Hoernle, 'A report on the British Collection of antiquities from Central Asia. Part I', JASB (1899), extra no. (Hoernle 1899).

4. Hoernle 1897, plates xi-xx.

5. Hoernle 1899, pp. 64-110.

6. Hoernle's Central Asian Register (IOR/MSS EUR F 302), no. 90.

7. A.F.R. Hoernle, 'A report on the British Collection of antiquities from Central Asia, Part II', JASB 70 (1901), extra no. 1 (Hoernle, 1901), p. 4.

8. Hoernle 1899, pp. 57-8.

9. For a detailed account, see Stein's Sand-buried Ruins of Khotan (1903), pp 447-59, and Ancient Khotan (1907). Typical Islam Akhun block-printed forgery.

The British Library, Or.13873/21

10. Hoernle 1901, pp. 1-5.

11. See S. B. Brysac, 'Last of the "Foreign Devils": Sir Aurel Stein's fourth foray into China was a humiliating failure. Who conspired to undermine the expedition and why?', Archaeology, Nov./Dec. 1997, pp. 53-9.

12. Cutting from The Times, July 1931, enclosed in IOR/L/PS/10/1218, file P.Z. 4100/31.

13. IOR/L/PS/10/1218, Enc. B to file P.Z. 4100/31: 'List of ancient objects brought to, or found on the surface by, Sir Aurel Stein during his journey from Khotan to Charkhlik'. This material and the photographs of the finds is discussed in detail by Wang Jiqing, 'Photographs in the British Library of documents and manuscripts from Sir Aurel Stein's fourth Central Asian expedition', The British Library Journal 24, 1 (Spring 1998), pp. 23-74.

14. Maj. George Sherriff 1898-1967. Vice-Consul at Kashgar 1927-30, Consul-General 1930-31.

15. IOR/L/PS/10/1218, file P.Z. 659/32. Report of 24 Nov. 1931 to His Britannic Majesty's Minister, Peking.

16. Photo 392/57 (prints) and Photo 392/52 (negatives). See Wang Jiqing's article and John Falconer, 'The photographs from Stein's fourth expedition: a footnote', The British Library Journal 24, 1 (Spring 1998), pp. 75-77.

17. See the introduction to P.O. Skjærvo, The Khotanese manuscripts from Chinese Turkestan in the British Library: a complete catalogue with texts and translations, to be published later in 2002.

18. See Falconer (quoted above).

19. Stein's original is in the Bailey papers. Stein also kept a copy (Bodleian Library, MS. Stein 64, f. 157) quoted by Wang Jiqing (see above).

20. Wang, op cit., p. 39 (Bodleian Library, MS. Stein 64, ff. 158-9)

21. Keriya is mentioned in Stein's letter of 27th April 1931 to Dr. L. D. Barnett, but none of the photos is labelled as being from there, and this is the only one without any site attribution.

Two 'New' Islam Akhun Forgeries & Forgeries Today

Two forged manuscript/blockprints have recently been rediscovered among Rudolf Hoernle's papers. They were in an envelope labelled by Hoernle 'Central Asian MSS. found by Lt. Col. Miles in his office.' Lt-Colonel P. J. Miles, was Special Assistant for Chinese Affairs at Kashgar during Macartney's leave, 1902-3, and they probably they date from about that time. They were brought to the India Office in December 1918, by the librarian, F.W. Thomas, with other manuscripts and papers from Hoernle's house in Oxford, after his death on 12 Nov. 1918.

Both are in very bad condition, and the writing is barely legible, but the first seems to contain repeated blocks of text in characters resembling Brahmi. It has been sewn with thread and is similar to many of Hoernle's other 45 blockprints now in the British Library 'forgery' section , as Stein called it,1 (Or. 13873/1-94). The second has been 'sewn' with two twists of paper and is even more difficult to make out. Each page contains a circle divided into eight sections containing writing, with a central rectangle. The pages that are legible do not seem to be identical.

Notes

1. Sand-buried ruins of Khotan, p. 477

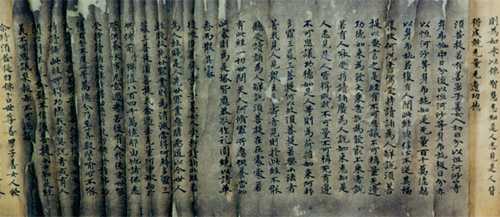

Right:Section of a manuscript offered to collectors and later found to be a recent forgery. It measures about 30 x 12 cm and consists of about 80 sheets of bark stuck together but with clear writing on the visible surfaces and small drawings on the back.

Forgeries Today

A series of suspected forgeries of both manuscripts and artefacts have recently come on to the open market. Thought by some to be produced in or near Quetta and then passed off as finds from archaeological sites in N.W. Pakistan one, at least, has fooled experts in the field. Radiocarbon dating of the bark manuscript shown above (and 3 others), offered by a dealer as a genuine manuscript in something resembling the Indus Valley or proto-Elamite script, showed the bark to be of recent date. The same dealer was responsible for the 'Persian' mummy find, the subject of a recent UK television programme (and found to be dated ca. 1999), and various other manuscript collections which have been bought by collectors in Europe. Not all of these, however, are believed to be forgeries.

One of the problems with these manuscripts is that they are being offered as unique, from periods for which there are few provenanced — and indubitably genuine — finds. Thus buyers have little with which to compare them. This is exactly the situation which Islam Akhun and the early forgers of Dunhuang manuscripts exploited in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

More Stein News

By a happy coincidence, Brigadier Barney White-Spunner, a member of the Sino-British Cross Taklamakan Expedition and publisher of Stein's Sand Buried Ruins of Khotan1, was posted to Kabul in January and was able to locate Stein's grave. Its condition was similar to that shown in the photographs in IDP News 18 taken by Victoria Finlay over 10 years ago. Brigadier White-Spunner has organised repairs and his photographs and a short report are given below.

The three year project to catalogue the Stein papers and photographs in the library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences came to a successful completion with publication of the catalogue and a very well-attended study day on Stein held at the British Museum. The success of the project was due in large part to the energy of its two instigators, Helen Wang of the British Museum, and Eva Apor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Helen Wang has also found time to publish another book on Stein. Details of these are given in the publications section.

Notes

1. A facsimile of the original 1903 edition of Stein's popular account of his first Central Asian expedition, Sand Buried Ruins of Khotan, has been published by Books for Travel in a limited edition of 500 copies, with photographs and maps and bound in the red cover of the original.

For details contact: http://www.booksfortravel.org.uk

or email: maria@booksfortravel.org.uk.

Stein's Grave

Aurel Stein's grave in the Gora Kabar (which literally means 'white graveyard') in Kabul has survived the recent fighting quite well. A group of Muhajedin removed the trees in the graveyard for firewood, but otherwise there has been little deliberate damage. When British troops arrived in January we discovered that the cross above the grave lost its top corner and the memorial stone was cracked, but this looked more like frost shattering than vandalism. This damage has now been repaired by a local stone mason and the grave polished. It is shown here following repair (left).

The graveyard has been cared for by the same Chowkidar, Rahimullah, (right) for a long time. He was unpaid for nearly twenty years during the various recent wars, and protected the graves during the worst excesses of the Taliban. Recompense has now been made by the Army and the British Embassy have salaried him again, in conjunction with other embassies in Kabul as people from many different countries are buried there.

The Gora Kabar lies at the northwestern corner of the Bimaru Heights in Kabul. It also contains 158 graves of British soldiers and their families dating back to the First and Second Afghan Wars, although many of their headstones have been lost. A severe frost in 1978 damaged the few remaining ones and those that could be rescued were placed in a line along the southern wall. We have renovated these and held a service of re-dedication in February. We have also dug a new well and put in an electric pump so that Rahimullah, who is now quite old, can restore the garden; built up the walls, to stop locals throwing rubbish over; diverted two domestic drains that seemed to empty on the southern side and had new gates made. With the Spring about to break, the graveyard looks as good as it has done for two decades.

The UK-Hungarian Stein Project

This joint project came to a very successful completion this spring with the publication of the catalogue (see publications) and the Stein Day at the British Museum.

Speakers at the Stein Day included the Project organisers — Helen Wang of the BM who spoke about her new publication, Sir Aurel Stein in The Times, and éva Apor, Head of the Oriental Collection, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, who spoke of Stein's Hungarian background. Other speakers who were members of the project included Lilla Russell-Smith (BM), John Falconer (British Library) and ágnes Kelecsényi (Budapest), the latter bringing along a recording made by Hungarian radio on New Year's Eve,1937 of Stein talking about Alexander Csoma de Kõrös who set out to find the cradle of the Hungarian people in Central Asia.

Other contributions to the very well-attended Stein Day came from Vesta Curtis (BM: Stein on old routes of Western Iran), Annabel Walker (biographer of Stein) and Shareen Blair-Brysac (on Stein's 4th expedition and Milton Bramlette). A small exhibition of photographs by Stein was organised by John Falconer.

The project gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the British Academy, the British Council (Hungary), the British Museum, the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund, the Hungarian Scholarship Board, and the Komatsu Chiko Foundation (Japan).

Conferences

The World of Central Asia

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Institute of Mongolian,

Buddhist and Tibetan Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Siberian Branch)

Ulan-Ude, Mongolia

13-16th June 2002

For details contact:

Dr. Buraeva Olga Vladimirovna

IMBTS, Russian Academy of Sciences

Sakhyanova St., 6,

Ulan-Ude, 670047, Mongolia

tel:3012 330318

email:imbt@bsc.buryatia.ru

Silk Road Art and Culture

The 6th Asian Studies Conference

Japan

Sophia University, Ichigaya Campus, Tokyo, Japan

22-23 June, 2002

For details contact:

Dr. Zsuzsanna Gulacsi

Department of Comparative Culture

Sophia University

Ichigaya Campus

4 Yonban-cho, Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo 102-0081, Japan

tel:(81)(3) 3238-4039

fax:(81)(3) 3238-4076

email: zgulacsi@sophia.ac.jp

http://www.meijigakuin.ac.jp/~kokusai/ascj

45th Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC)

Budapest

23-28 June 2002

For details contact:

Secretary General PIAC

Goodbody Hall 157

Indiana University

1011 E. Third St., Bloomington

Indiana 47405-7005

USA

Fax:+1 812 855-7500

email:

sinord@indiana.edu

Turfan Revisited:

The First Century of Research Into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road

Berlin, Germany

8-15 June, 2002

This conference will coincide with a major international exhibition at the Museum of Indian Art in Berlin-Dahlem

For details contact:

Professor Dr Werner Sundermann

Akademievorhaben Turfanforsdhung

Berlin-Brandenburgische

Akademie der Wissenschaften

Unter den Linden 6

D-10117 Berlin, Germany

Tel: +49 30 20370 472

Fax: +49 30 20370 467

email:sundermann@bbaw.de

The Central Asian Studies Society

3rd Annual Conference

University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

17-20 October 2002

For details contact:

Center for Russia, East Europe and Central Asia

University of Wisconsin

210 Ingraham Hall

Madison, WI 53706

USA

Tel: +1 608 262 3379

Fax: +1 608 265 3062

Email:creeca@intl-institute.wisc.edu

http://www.wisc.edu/creeca/

Additional information about past and forthcoming CESS Annual Conferences is available at the CESS website:

http://www.fas.harvard.edu/cess/

Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road:

2nd International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites

Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China

August 25-29, 2003

For details contact:

Kathleen Louw

The Getty Conservation Institute

1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700

Los Angeles, CA 90049, USA

Tel: 1-310-440 6216

Email:klouw@getty.edu

http://www.getty.edu/conservation/

Cultures of the Silk Road and Modern Science Conference in commemoration of the Otani Mission to Central Asia

Ryukoku University, Kyoto, Japan

September 8-13 2003

This conference will compromise symposia concentrating on different aspects of the theme, as below. The opening day, 8th September, is when the first Otani

expedition organised the caravan at Osh in 1902.

9th: 'Buddhist society on the Northern Silk Route'

10th: 'Buddhist Arts in Kucha'

11th: 'The Southern Route and the Niya Ruins'

12th: 'Analysis and Preservation of Central Asia Finds (IDP Conference)

For details contact:

Professor Kudara Kogi

Department of Buddhist Studies,

Faculty of Letters

Ryukoku University, Shichijo Omiya

Kyoto 600-8268, Japan

Tel: +81 75 343 3311

fax: +81 75 343 3319

Email:saiiki@let.ryukoku.ac.jp

Fieldwork Opportunities

Khazarian fortress in the Lower Don Region

Details of a new fieldwork opportunity - the excavations of the Khazarian fortress in the Lower Don region - can be found on a special page:

http://www.da.aaanet.ru./volunteer/volunteer_en_fr.htm

This is part of the newly-mounted website of the journal, Donskaya Arkheologia, http://www.da.aaanet.ru (in Russian and English)

Study Project in Mongolia

The Cultural Restoration Tourism Project (CRTP) is a non-profit organization established to restore and preserve culturally significant buildings and artefacts around the world. Our current project is the restoration of a Buddhist temple at the Mongolian monastery of Baldan Baraivan. The restoration will include building restoration, infrastructure and community building. CRTP is planning to use the latest techniques in sustainable development to rebuild a community that can support itself with limited impact on th environment. During the restoration process we will be looking for volunteers to donate time to the project. Scholarships are available to interested students. In addition to our tour packages, CRTP will be offering three full-summer internships to individuals. There are no area of study requirements for the internships.

For details contact: Mark A. Hintzke, Director

Cultural Restoration Tourism Project

email: crtp@earthlink.net

http://www.crtp.net

Publications

From Nisa to Niya: New Discoveries and Studies in Central and Inner Asian Art and Archaeology

Madhuvanti Ghose, Lilla Russell-Smith and Burzine Waghnar (edd.)

Saffron Books, London 2002

ISBN: 1 872843 30 1

This is the first volume of the new Circle of Inner Asian Art (CIAA) series taken from lectures hosted by CIAA.

For details contact:

Saffron Books, Eastern Art Publishing,

PO Box 13666, London SW14 8WF.

tel: +44-[0]20-8392-1122.

fax: +44-[0]20-8392-1422.

email: saffron@eapgroup.com

La Serinde, Terre d'Echanges: Art, religion, commerce du 1er au Xe siecle

Actes du colloque international

Galeries nationale de Grand Palais

13-15 fevrier 1996

November 2001,

ISBN 2-11-004281-8, 69.64 Euros,

For details contact:

La Documentation francaise

29-31 quai Voltaire, 75344 Paris, France

tel: +33 1 40 15 70 00

fax: +33 1 40 15 72 30

http://www.ladocfrancaise.gouv.fr

Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries

British Library Studies in Conservation Science: 3

Susan Whitfield (ed.)

The British Library, London 2002

352 pp., 105 b/w, 12 col. ills.

ISBN: 0 7123 4631 7, £36 (pb).

For details contact:

Email:turpin@turpin.com

In US:utbooks@utpress.utoronto.ca

order online

Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

British Museum and Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Budapest 2002

This is the first catalogue of the very important collections of Stein's photographs, correspondence, documents, articles, offprints and miscellaneous paper which are kept in the Library in Budapest.

For details contact:

Helen Wang

Dept of Coins and Medals, British Museum

London WC1B 3DG, UK

email:hwang@thebritishmuseum.ac.uk

Sir Aurel Stein in the Times: a collection of over 100 references to Sir Aurel Stein and his

extraordinary expeditions to Chinese Central Asia, India, Iran, Iraq and Jordan in The Times newspaper 1901-43

Helen Wang (ed.)

Saffron Books, London 2002

164 pp., 19 ill. and maps

ISBN 1 872843 29 8

£19.50 (inc. p&p to UK address)

£22.50/US$32 (to non-UK address)

For details contact:

Saffron Books, Eastern Art Publishing,

PO Box 13666, London SW14 8WF.

tel: +44-[0]20-8392-1122.

fax: +44-[0]20-8392-1422.

email: saffron@eapgroup.com

Professor C.S. Upasak

Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies

fax: 91 542 585150

email: cihts@hotmail.com, cihts@yahoo.com

http://www.cihts.ac.in

Buddhist Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection

Volume 2

Jens Braarvig, Paul Harrison

Jens-Uwe Hartmann, Kazunobu Matsuda and Lore Sander (edd.)

400 pp., 56 plates

NOK 980, (approx. US$125)

To order:

email: hermesac@online.no

email: (in Japan): malshow@beige.ocn.ne.jp

Dunhuang Research Institute

The Commercial Press, Hong Kong

pp. 240-272; format: 210 x 285 mm; hardcover with case

As a subscriber to IDP News you can order single copies of this series at 10% discount; mini-sets of 3 or 4 copies at 15% or the full set of 11 copies published to date at 20% discount. IDP will receive 15% of the order value from the publishers.

For details contact:

email: sales@commercialpress.com.uk

quoting 'IDP Offer'.

Central Eurasian Studies Review

No. 1 (Winter 2001)

This is the first issue of a scholarly review of research, resources, events, publications and developments in scholarship and teaching on Central Eurasia. It will appear three times annually and is distributed free of charge to dues paying members of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (CESS). Institutions may subscribe at a rate of US$50 per year.

The Review is also available to all interested readers via the web.

http://www.fas.harvard.edu/cess/CESS_Review.html.

Fayuan (Source of Dharma)

No. 19 (Dec. 2001)

Contributions to this issue include:

Yang Zengwen, 'Study on the Formless Precepts of the Dunhuang Text of the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch'

Ma De, 'Social Significances of Inscriptions of Dunhuang Manuscripts'

Da Zhao, 'Study on the Dunhuang Text P2039V: Ode to the Diamond Sutra'

For details contact:

Zhongguo Foxueyuan

7 Fayuansi Qianjie, Xuanwu District

Beijing 100052

tel. & fax: +86 10 83517182

email: Fayuanbianjibu@263.net

Project News

People

Colin Chinnery (left), Project Manager with IDP, left for a new life in China at the end of February. We were very sad to see him leave but wish him well in the future.

Colin started with the International Dunhuang Project in January 1998 on a three-year grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund to set up the digitisation programme, which he did very successfully. In 2001 he was promoted to become IDP Project Manager with responsibility for China and other collaborations with institutions in the UK and abroad, funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England.

During his time with IDP, Colin designed and wrote the very popular and informative bookbinding web pages and also designed and implemented the map interface for the web database. In addition, he worked on a new GIS interface for IDP and the British Library. IDP is currently recruiting for a replacement and details of the new member of the team will be given in the next issue.

Sam van Schaik received a promotion to become IDP Project Manager responsible for the Digitisation Studio and Tibetan material. His post is funded by a three-year Arts and Humanities Research Board (AHRB) grant and he will be concenrtating on cataloguing the Tibetan manuscripts from Dunhuang and supervising their digitisation and entry on to the database.

The AHRB project is a collaborative project based at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Jacob Dalton was appointed by SOAS as a Research Fellow to work together with Dr van Schaik on the cataloguing.

Virginia Lladó-Buisán and Barbara Borghese joined the IDP team in March to work full-time on conservation of manuscripts to be digitised as part of the Mellon programme. The Mellon Foundation generously provided a grant for their work for three years.

Yoriko Chudo, a conservator from Japan, is currently working on Tibetan illustrated material from Dunhuang and will come back to the Library in July as a research fellow to work on the Tibetan material from Dunhuang.

Kate Hampson and Colin Chinnery met with staff at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in January to discuss possible collaboration on the digitisation programme.

Visitors

Left:The British Library Chief Executive, Lynne Brindley, and Head of the Chinese Section, Frances Wood, with the Cultural Counsellor, Yan Shixun, and First Secretary, Pu Jubao, from the Cultural Section of the Chinese Embassy in London

The new Chinese Cultural Counsellor to London, Yan Shixun , his wife, Pu Jubao (First Secretary (Cultural)), and Huang Peibin (Third Secretary), visited the International Dunhuang Project at the British Library on 30 January. After a tour of the Library and an introduction to the IDP Digitisation programme they had tea with the Chief Executive, Lynne Brindley.

5th Conference

The Fifth Conference on the Preservation of Central Asian Material is being held under the auspices of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities with the National Museum of Ethnography/the Sven Hedin Foundation in Stockholm, 17-19 October, 2002. It will concerntate on practical workshops on paper and textile conservation, with some general reports and scientific papers. Participation is limited firstly to invited people and it is hoped that the papers may be published. Professor Hakan Wahlquist and Anna-Grethe Rischel came to London to discuss the conference in March.

China Office

An update on the IDP Project in China is given in the Chinese news-sheet.

Joint Promotion

Commercial Press (Hong Kong) and IDP have agreed a joint promotion for the Dunhuang caves series. (see Publications) A flyer was sent with the previous newsletter. The series are offered at a special discount to IDP members and IDP receives 15% off all sales. Readers are encouraged, therefore, to take advantage of the discount and to help to support IDP.

Next Issue

The next issue of the newsletter will be devoted to the Swedish expeditions to Central Asia led by Sven Hedin, in preparation for the 5th conference to be held in Stockholm.